“Oh, shit.”

Never entirely comforting words to hear from your captain, but utterly appropriate. I heard it too, after all—the cascade of rumbling and ripping, rising gradually in pitch in the span of seconds—the sound of thousands of pounds of sailcloth shredding.

Unlike my captain, however, I had yet to actually see it—or rather, them.

From where I stood, I watched his head turn further to the right, eyes wide.

“Oh, no.”

And there was the other it.

On an unfavorable jibe in a gale in the English Channel, we simultaneously tore not just our foresail but also our mainsail. One was split in half, while the other was reduced to two-thirds.

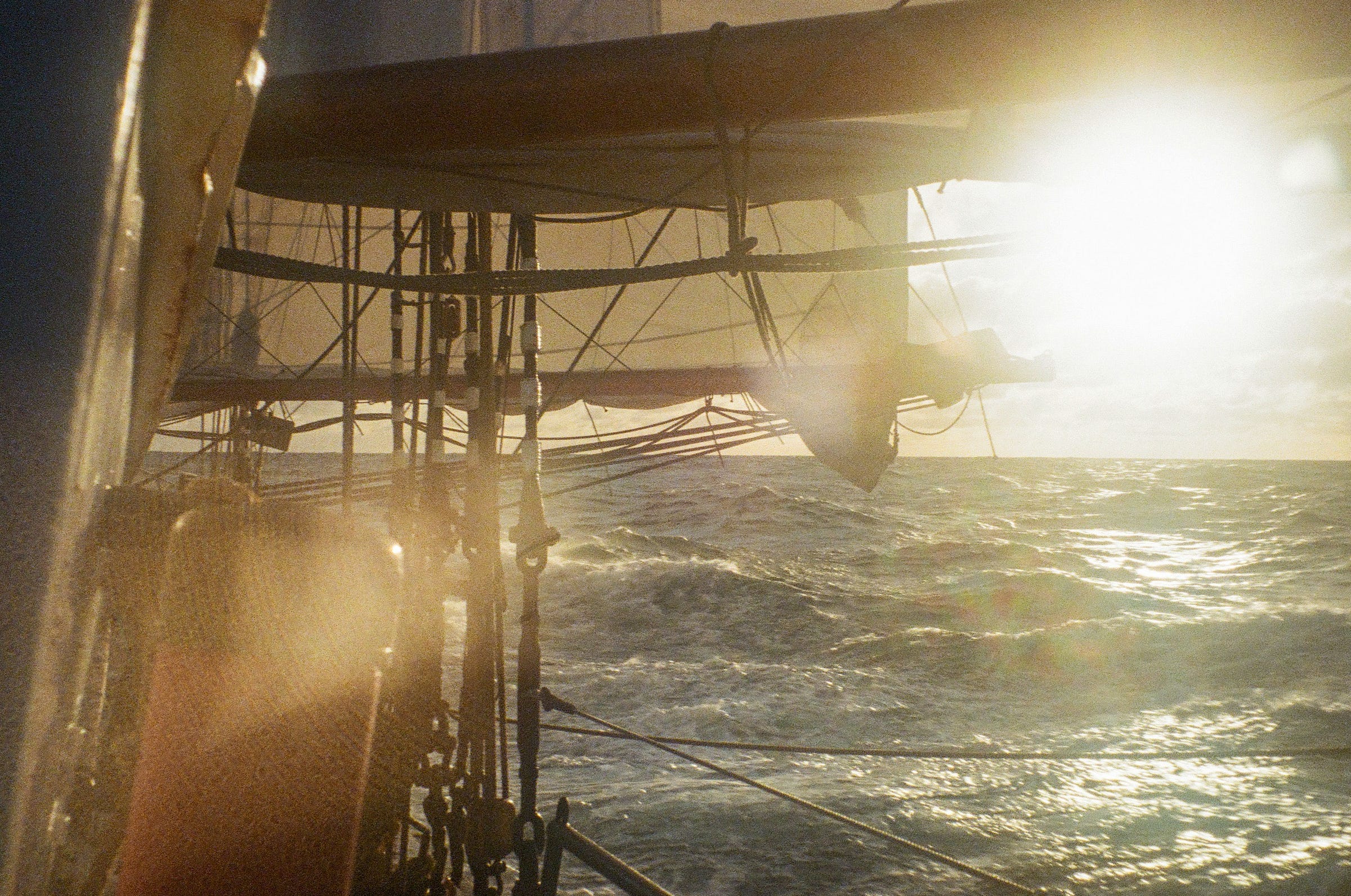

Acutely aware that we were nearing one of Europe’s busiest shipping lanes, we uneasily jostled in the choppy waters between France and England. As the sun began to set, our situation was looking less than ideal.

This mishap was especially concerning, given that our vessel—a 105-year-old gaff-rigged schooner—carried no extra sails. Our engine, which was only to be used in emergencies (as this was a sail cargo vessel) had a top speed of no more than 5 knots on a flat sea with no current.

And here we were at 8 p.m., caught in particularly large seas at a geographical chokepoint, where currents were recorded at speeds of up to 13 knots. Our main boom thrust in and out of the water, while hundreds of pounds of newly wet and ruined sail dragged off our starboard side.

A calming way to end my watch.

But, as the saying goes, many hands make light work. Within minutes, rubber boots—and the newly awakened shift that wore them—clambered across the lurching deck. Our bosun, an emergency nurse and Ph.D. from France (a woman accustomed to high-stress situations), strapped into a harness and began to scale the main mast. The damage was worse than initially thought; several mast hoops also needed repair.

The captain and first mate began issuing orders. One took the wheel to steady the ship amid the bounding rollercoaster of waves, while the rest of us moved quickly, each task aligning with the next.

Shortly, our many hands began to work as one.

On a vessel of this size and age, there are no automatic winches, no buttons to push to hydraulically reel in the boom, no autopilot. Instead, everything is as it was designed 100 years ago—the boat a living, breathing artifact that requires living, breathing bodies to sweat and exert themselves to make the hulking beast do as it’s told.

Hand over hand, soon we were hauling sheets to the rhythmic calls of “2, 6,” rocking our bodies back and forth to hold a beat that somehow took our individual strength and multiplied it by three.

Eventually, we did tame the beast.

In the span of an hour, our foresail—broken beyond repair—was doused and, though packed somewhat haphazardly, safely returned on board. The main gaff sail, a shadow of its former self, could be reduced to its third reef—offering little power but at least some balance.

Adrenaline drained, heartbeats slowed, and our ship was once again under control.

The shrunken mainsail and a jury-rigged foresail, made from two jibs, would miraculously carry us the rest of the way to the Netherlands, where we would deliver sustainably sourced and, most importantly, sustainably shipped goods to Northern European markets.

While this was not a particularly average day on this transatlantic clean shipping voyage, the term “average” hardly applies in this line of work. Wonders, and sometimes frights, are a part of the daily rhythm of life onboard a sail cargo vessel.

The term sail cargo refers to the fleet of wind-powered vessels—some restored, others newly designed—that transport freight across oceans with little to no carbon footprint. Many of these vessels are traditional cargo ships from the early 20th century, such as the Avontuur, the Danish-built schooner I sailed on.

Any mariner who has navigated open seas or busy coastal shipping lanes understands that the ocean is a vast, unwritten network of highways. Though invisible to most of the public, it hums with activity. Cargo vessels, oil tankers, and resupply ships clog what was once thought to be an endless, open seascape. As marine journalist Rose George noted in her book Ninety Percent of Everything, more than 90 percent of the world’s commodities—from coffee to cell phones to medicine—arrive via these unmarked watery roads, largely by cargo ships.

This movement of goods is not without cost. The majority of cargo vessels traversing our seas run on carbon-heavy fuels like bunker oil, meaning every shipment leaves an environmental toll in its wake.

According to Transport & Environment, one of Europe’s leading clean energy organizations, cargo shipping currently accounts for 3 percent of global carbon emissions. That number is projected to rise to 10 percent by 2050.

The mission of the sail cargo movement is simple: to offer a sustainable, wind-powered alternative for bringing these goods to market.

The sustainable shipping industry has been steadily growing, reviving traditional vessels that now operate on modern shipping routes. When I joined the Avontuur crew in Horta to prepare for our passage to Europe, I was surprised to find another sustainable sail cargo vessel, the Ide Min, docked alongside us. Each season, several companies complete transatlantic voyages, delivering coffee, rum, and other non-perishables from Latin American markets to Europe, while exchanging crew members at each port stop—Horta being a frequent port of call.

As one might expect, the crews who choose to work on these historic vessels are often misfits in the broader maritime community—not unlike the ships themselves.

It takes a particular kind of individual to want to cross the Atlantic Ocean on a vessel that offers little comfort—recall, most of these vessels are relics from the early 20th century.

Many of those who work on these vessels are young, not yet accustomed to demanding luxuries like hot showers or private rooms. Sharing quarters is the norm on working ships, and on the Avontuur, that meant sharing a foxhole with 16 other bunks, each occupied by a salt-stained body, sometimes sopping wet from the rain, other times slightly singed and peeling from sunburn. Most often, snoring.

On the Atlantic Ocean, all four seasons (and little sleep) abound.

Though a German-run boat, the Avontuur's crew consisted of a broad range of nationalities and characters: German, Italian, Colombian, American, French, Flemish, Swiss, and English. Many people onboard had joined the sail cargo industry due to the climate guilt they felt from intercontinental air travel, with sailing offering a slower yet more carbon-neutral solution.

Others joined for a sense of adventure, seeking a year spent in a rigging harness rather than behind a desk. Some sailed to reconnect with loved ones. A particularly warm woman, who had already crossed the ocean from east to west, was joined by her father, who had Parkinson’s disease. Together, they sailed back to Europe to fulfill his dream of crossing the Atlantic.

In all, our voyage from Horta to the Netherlands took about three weeks. Days at sea blurred together, passing all at once or hardly at all. As long-distance sailors know, time feels slippery on the open ocean, broken only by meals, watch shifts, and the occasional burst of novelty. For us, those moments of discovery often manifested in the form of wildlife.

While traveling purely by sail is albeit slower, the absence of engine noise invites special kinds of visitors.

Often, I heard them before I saw them—a sudden splash ahead, a sharp cry from above—followed by the shimmering blur of fins zigzagging through the bow wake or the shadow of wide wings momentarily darkening the deck. Seabirds and cetaceans offered ripe entertainment in lieu of cell phone service.

Dolphins became so commonplace on our route to Europe that our second officer dubbed them “rats of the sea”—a name that, while unfair to their beauty, adequately captured their abundance.

On particularly special days, shouts of “Whale!” would ring across the deck. In an instant, the awake crew (or the newly roused) would rush leeward to catch a glimpse of passing pods of pilot whales, their black, bulbous heads cresting in and out of the water, bound for destinations unknown.

And then there are the special moments reserved for one’s own company: a particularly stunning sunrise or sunset, a quiet spell at the helm when William Ernest Henley’s poetic words, “I am the master of my fate, I am the captain of my soul,” begin to make sense, or a sun-soaked deck nap so blissful you wonder how sleeping on land will ever compare again.

Two nights while at sea, bioluminescent jellyfish bounced alongside the hull of our slow-moving ship, emitting explosions of yellow light before drifting onward—a true gift.

In the seemingly endless waters of the Atlantic, conversely, the world becomes delightfully small. The true beauty of sailing through this watery desert lies in how, for a brief moment, the busyness of life, future plans and past mistakes, quiet to the singular mission of the boat: arriving at port.

Pleasure is found in the cadence of nature, in camaraderie, in routine, and in the rare gift of boredom, where you’re forced to sit with nothing but the present.

Funny how, in our minuscule existence—just one ship in a vast ecosystem—this humility compelled us to look inward.

Rather than dissolving into the asymmetry of our untethered state, it was structure and the day-to-day rhythm with the crew that maintained the delicate boundary between the human world and the animal kingdom, between pleasure and bedlam.

Strange forms of society pop up on long voyages. Onboard the Avontuur, our society manifested in a series of extracurricular activities: workout club, podcast club, book club, no-club club—any excuse to add a moment of structure and entertainment to the weeks.

Nowhere onboard did anyone have two copies of the same book, so naturally, this literary club evolved into a more of a modern twist on cavemen sharing stories around the fire.

“Here is the plot of my novel; now you show me yours.”

In practice, podcast club was a haphazard affair: lying together on deck, our heads circled around someone’s phone as we tuned into whatever forgotten audio gems had been downloaded into the depths of their radio library.

Strange superstitions likewise abound while at sea: no bananas on boats, no whistling, avoiding the number 13. And while most sailors are inherently superstitious, tall ship sailors—those who work on traditional sail cargo vessels—are in a league of their own.

Every Sunday, at our captain’s reception, we were ceremoniously offered a swig of rum, the Avontuur being a dry ship, despite the tens of thousands of pounds of liquor in its hold. But before anyone could drink, we first had to appease Rasmus, the Nordic wind god—who, with his apparent thirst and fickle temperament, required a weekly cup of firewater to soothe his mercurial moods.

The first cup of top-shelf spirits was always thrown overboard.

Who wants to bet against the gods, anyhow?

While appeasing Rasmus became part of our weekly ritual, it also served as a reminder of a larger truth aboard the Avontuur: no task, no matter how small, can be done alone. Just as we all had to satisfy ancient maritime superstitions, the operation of the ship likewise demanded the same collective effort.

The great beauty of these historical vessels, and in the sail cargo movement more broadly, lies in their reliance on community strength. No sail can be raised by a single person, and no technology can replace the necessity of working together.

That sense of collaboration applies to more than just the vessel. It applies to the entirety of the ship’s mission, to how our supply chain operates, and to how our individual choices affect everyone.

Despite a literal ocean of separation, the goods carried by sail cargo vessels are often bought from and sold by small sellers.

Upon arrival in the EU, sail cargo coffee, for example, can be purchased from local stores and small businesses, fostering relationships between people and places rather than promoting faceless transactions at a megastore self-checkouts.

Small growers also benefit. Unlike large corporations that source raw materials from foreign conglomerates operating in the Global South, the wind-powered network connects small-scale farmers with roasters across the sea. In this system, the exploitative interconnectivity promoted by neoliberal structures is momentarily replaced by a more personal and sustainable bond.

The Avontuur exemplifies this shift. As it continues to crisscross the Atlantic, picking up new crew, it stands as one vessel among many in the growing sail cargo industry.

This ship, a small part of a much larger picture, serves as a reminder of a different way our commodities can reach us and how communities might function differently when we take time to consider our broader environmental landscape.

This boat is proof that when we chart more meaningful courses—physically, socially, and environmentally—we can learn to recognize our collective responsibility and work together, though we may be soaking wet and winchless.